They say the feeling of pure silk against the skin is as close to heaven as it gets. But it wasn’t the lightweight material I touched that day. My body carried over 30 kilograms of heavy garments, decorations, and headpieces. I was wearing a Japanese Kimono in Japan. I had only dreamed of dressing up in a traditional Japanese kimono before, but now, for just one day, my dream has come true.

Almost two decades ago, I became obsessed with the Japanese lifestyle. I studied Japanese manners and customs, spent countless evenings reading about the tea ceremony and the Japanese culture. I even learnt basic Japanese and continue to take lessons to improve on my language skills.

When you think of Japan, you inevitably imagine people wearing a traditional kimono, the Japanese traditional attire. Of course, nowadays, western clothes or yukatas are used for everyday wear. Nevertheless, the beauty of a Japanese kimono remains seen as a great work of art, usually hand sewn made with exceptional skill and care.

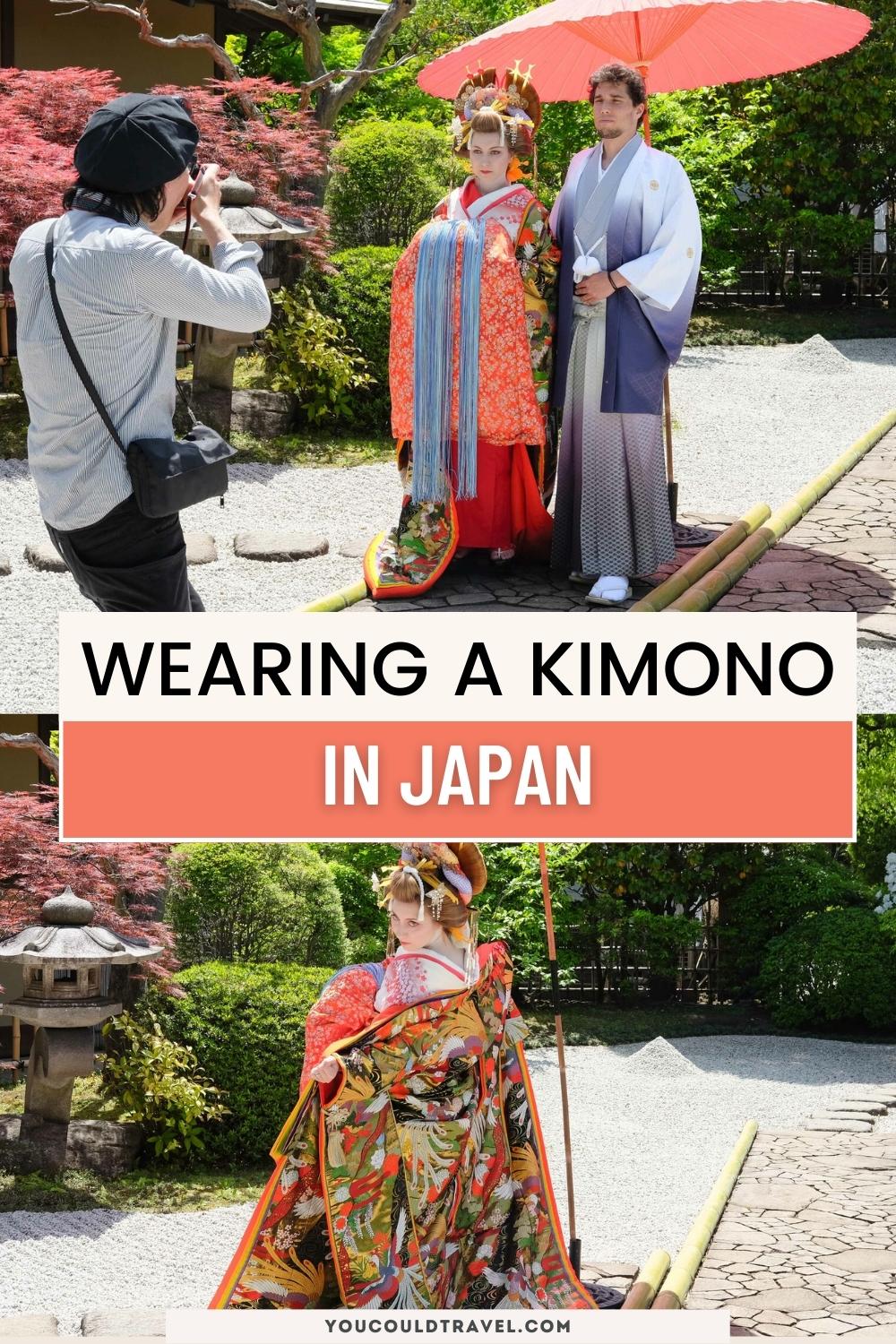

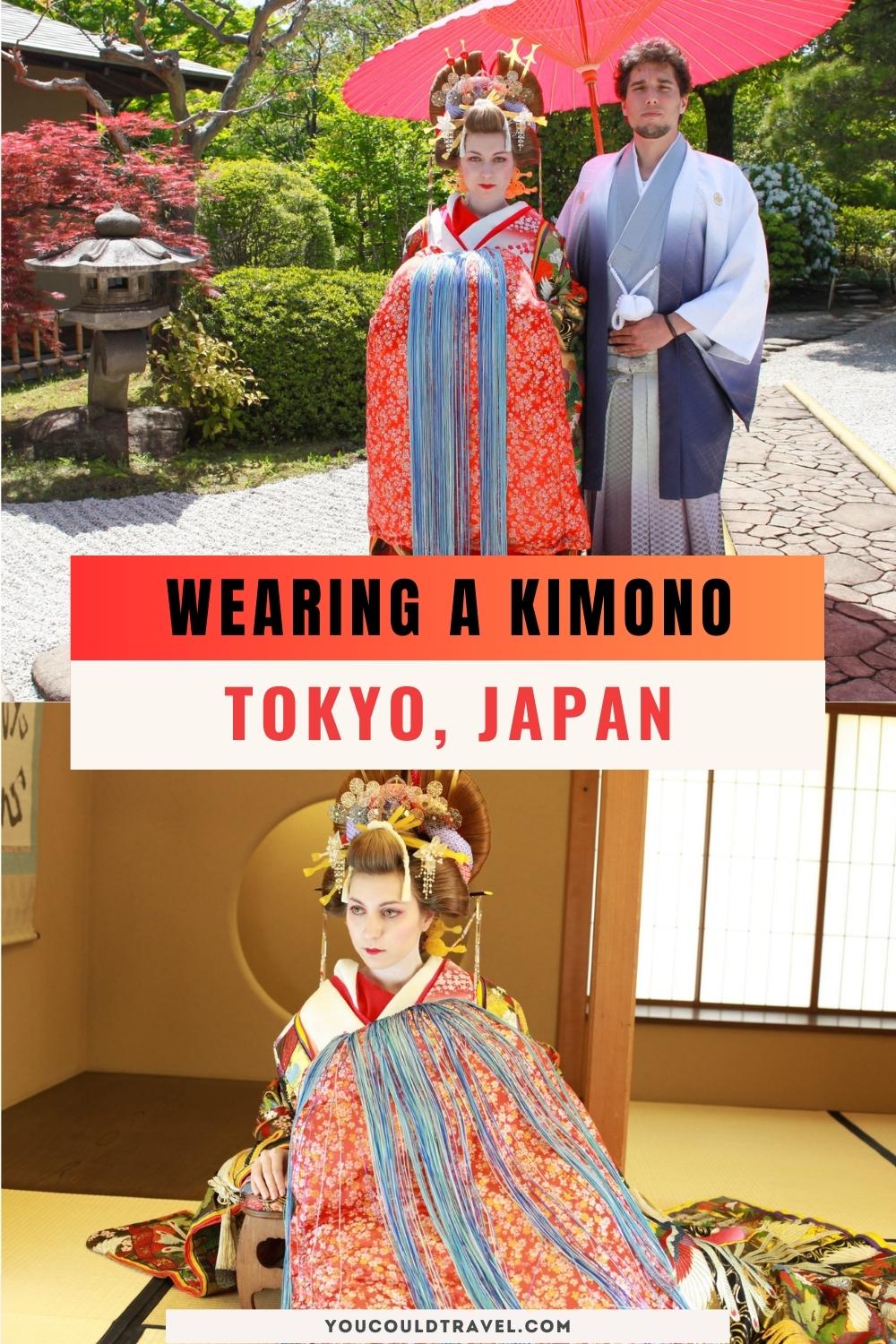

In this guide, I will tell you about my experience wearing a kimono in Japan and what it’s like to be in Japanese traditional clothes. Both my husband and I wore kimonos, so I will explain in details the differences between a Japanese kimono for men and women, as well as the culture behind wearing such fine garments.

Book your kimono experience in Japan:

Table of Contents

Wearing a Kimono in Japan

A day of anticipation and wonder unfurled before me, my heart aflutter with a curious blend of excitement and nerves. We journeyed in an old, white minibus, its lingering scent of cigarettes and aura of untold tales silently accompanying us. I remained a quiet observer throughout our voyage, anticipation building with each passing moment.

At last, we arrived at the doorstep of a hidden world, nestled beside a breathtaking Japanese garden. A bamboo fence stood sentinel, as maple and cherry trees presided over a serene Zen garden. Stepping through the doorway, I was ushered into a secret Japan, where tatami floors whispered beneath my feet, and sliding doors and paper windows concealed a realm of enchantment.

Beaming faces greeted me, as a group of women led me into a room filled with exquisite kimonos. With practised grace, they chose the perfect kimono dress, Japanese robe, and kimono obi that seemed to have been waiting just for me. My husband and our guide were kindly asked to wait outside, as the women’s excitement bubbled over, eager to begin the magical transformation.

What to expect from the Oiran Japanese kimono experience

In a room filled with warmth and camaraderie, I was invited to disrobe and don a white robe for the upcoming transformation. The atmosphere was brimming with the joy of a secret sisterhood, and I felt at ease, as though I had known these ladies for a lifetime. Upon catching sight of the tattoo on my back, they giggled with delight, gathering around to admire the inked artwork. “Kawaii” they exclaimed, their curiosity piqued. Despite my awareness of the taboo surrounding tattoos in Japan, their light-hearted acceptance put me at ease, even more so when one of the ladies revealed her own hidden, charming tattoo.

Whisked away to a new room with a picturesque view of the tranquil pond, I watched as turtles and elegant Japanese carp meandered through the water, framed by the verdant foliage. The scene embodied the perfect harmony of beauty and serenity.

The ladies, their smiles contagious, warned me that the preparation for wearing a Japanese kimono would take a few hours. One of them delicately applied white paint usually used in Kabuki theatre to my neck and nape, a region revered for its sensuality in Japanese culture. Her strokes were both gentle and practised, leaving two alluring stripes of bare skin exposed.

As the makeup was gently applied, my European features transformed into a porcelain-like visage, reminiscent of a delicate doll. With meticulous care, red eyeshadow and black eyeliner were applied, further accentuating the enchanting illusion. My lips, touched by a rich, intense lipstick, took on the appearance of classic Japanese makeup, reflecting the Japanese ideal of beauty that celebrates the allure of smaller, refined lips.

The most time-consuming part of the process was the intricate styling of my hair. Long hair was preferred, but fear not, extensions were available to accommodate all. My natural hair was enhanced with added volume and shape, while a colour-matched wheel was skilfully wrapped in my tresses.

“Women suffer for beauty,” the Japanese lady told me. “They used to do this hair once a week and sleep on a hair pillow. Very difficult until you get used to it.”

The weight of the elaborate style challenged my neck, but I couldn’t help but admire its magnificence, secretly wishing I could wear it every day.

Over the next half hour, they adorned my locks with a dazzling array of coloured threads, crowns, and myriad pins, each detail adding to the enchanting tableau.

Dressing in a Japanese kimono

The moment to don a kimono dress had finally arrived, a dream I had cherished for countless years. Wearing a kimono in Japan promised an experience of delightful heaviness, as I was told, a sensation I could hardly fathom, considering the weight of my elaborately styled hair.

My journey began with the wearing of a white Nagajuban robe, a practical, machine-washable garment that protects the kimono from dirt. Typically white and visible only at the collar, the Nagajuban for an Oiran featured a triangular fold that revealed a striking red collar. A Datejime was used to secure the robe.

The kimono I chose was a furisode, its swinging sleeves cascading between 39 and 42 inches (about 100 cm). The heavenly touch of the silky fabric, adorned with a mesmerizing red and white cherry blossom motifs, left me spellbound.

As an Oiran, my kimono was worn in the Ohikizuri style, or dragging tail. The Uchikake over-robe draped elegantly behind me, setting me apart from a Geisha.

The Manaita Obi tied at the front served several purposes: to enable easy untying in bed, to flaunt the client’s wealth, and to display the Oiran’s vanity.

To complete the ensemble, a stunning Uchikake awaited me. Reserved for brides or stage performances, this highly formal kimono trailed along the floor, its heavily padded hem adding to the grandeur. The layers weighed over 20 kilograms, demanding strength and poise to navigate in such exquisite attire without faltering or discomfort. The dedication required by this way of life was awe-inspiring.

As I ventured into the garden, I wore Oiran Getas, their towering height presenting a challenge to my balance and grace. For the first time in my life, I felt what it was like to be really tall.

Japanese kimono for men

In the midst of my enchanting transformation, my husband too embarked on his own adventure, being adorned in a kimono of his own.

His attire was more modest, comprising just five pieces and no accompanying footwear. He described the kimono as lightweight and comfortable, exuding a sense of luxury.

With great enthusiasm, he embraced the distinctive Tabi, ankle-high divided-toe socks, and Zōri, traditional sandals akin to flip-flops, worn by both men and women in Japan.

Wearing a kimono in Japan for men is a different experience. Here is what a formal traditional men’s kimono consists of:

- Kimono: The main garment, which is a long, T-shaped robe with wide sleeves and a straight-lined silhouette. My husband’s kimono was made of silk and had a more understated design compared to my kimono.

- Nagajuban: A thin undergarment or under-robe worn beneath the kimono. It serves to protect the outer kimono from sweat, as well as providing an additional layer for comfort and modesty.

- Obi: A wide sash or belt used to secure the kimono in place. Men’s obis are narrower and less ornate than those worn by women.

- Tabi: Ankle-high, divided-toe socks worn with traditional Japanese footwear.

- Zōri: Zōri are flat sandals made from materials like straw, cloth, or leather.

As this was a formal kimono event, he also wore a Haori (a formal jacket), a Haori Himo (Japanese Traditional tasselled cord) and the Hakama (a wide-pleated skirt-like garment).

Our experience wearing a Japanese kimono

Once we were ready and the room impeccably arranged, we took turns posing for the camera. Guided by precise instructions on how to sit or stand, and position our arms and necks, we felt like celebrities as countless photos were snapped.

Later, the photoshoot moved to the back garden, where I was elevated on my oiran geta. You can see that in the pictures standing right next to my very tall husband, I’m almost as tall as him.

With the assistance of three people, I managed to walk and strike poses gracefully. I felt beautiful and splendid.

Curiosity piqued, patrons from the tea house requested to take pictures with us. We continued our enchanting journey to the front Zen garden, perfectly staging our Japanese kimonos. Passers-by couldn’t resist sneaking peeks over the fence and snapping their photos. It was delightful to be the subject of such fascination.

We spent over an hour capturing memories from every angle, knowing we’d have a treasure trove of photos in our exquisite kimonos. The experience made me feel even more cherished than on my wedding day.

Finally, content with our photoshoot, we returned to disrobe. The attendants gently removed my makeup, signalling the end of my diva moment.

Ravenous after so much excitement, we were treated to a bento box filled with tasty sushi and rice. Oh, the joys of Japanese hospitality! How I wished I could have moved into that enchanting tea house, basking in the attentive care, preparing for photoshoots, and savouring the exquisite cuisine every day.

What are the secrets behind the traditional Japanese kimono?

During our leisurely lunch, we talked about the history of Japanese kimonos, Oiran, and Geisha. Before this enlightening experience, I had scarcely known the distinctions between Oirans, Geishas, and Maikos. There was much to uncover.

Courtesans were called Tayū or Oiran, and they thrived between 1643 and 1763. These courtesans were regarded as yūjo, or “women of pleasure” akin to prostitutes. It’s important to note that Geishas and Oiran are not the same thing. While they worked together in the entertainment districts, Geishas were selling their skills and not their bodies. Oiran, on the other hand, were known courtesans. The Oiran profession vanished around the Edo Period.

Even though Oirans were known courtesans, the government conferred upon them the prestigious Senior Fifth Rank, equivalent to a feudal lord. The red collar they wore symbolized their esteemed status.

A brief history of the oiran

I pondered how girls became oiran. The truth is, most had no choice. Coming from impoverished farming and fishing villages, many were sold for money. Lower-ranking samurai often sold their wives and daughters to repay debts. Sometimes women were deceived and sold by unscrupulous men. Some girls were even kidnapped and forced into the profession.

There were three prominent red-light districts known in Japan: Yoshiwara, a renowned yūkaku in what is now Tokyo, which emerged in 1617. It stood alongside Shimabara in Kyoto, established in 1640, and Shinmachi in Osaka.

Once within a red-light district gates, there was no turning back. Escapees were hunted, captured, and tortured. The selling price of these women ranged from approximately 300,000 yen (approx £2000) to 1.8 million yen (approx £10,500). Only a select few reached the coveted Oiran status. Most began their lives as harlots around 16 or 17 years old, and many needed a daily client to survive. Girls with less desirable features often became house managers, while the more alluring advanced to Oiran.

The rules of service for prostitutes required them to work from about 16 or 17 until they were 28, referred to as the “10 years of suffering death”. There were three ways to leave this harrowing life: repay their debt during the “10 years of suffering death” or have someone else redeem their debt and future earnings, or meet their demise. However, many remained in the house, unable to escape their debt.

Those with enchanting features were meticulously trained to become Oiran, receiving first-class education in classical literature, Japanese poetry, calligraphy, tea ceremony, samisen, Japanese harp, and the games of go and shogi. Engaging with an Oiran was no simple task, as clients had to demonstrate their wealth and offer expensive gifts, such as lavish kimonos.

The first encounter with an Oiran involved her appraising the client from a higher seat, exchanging not a single word. If the client was deemed unsuitable, a second meeting would never transpire. On the second encounter, the Oiran would approach closer while continuing her evaluation. Finally, during the third meeting, the Oiran would become acquainted with the client, and after receiving a handsel, she would consent to sleep with him. The client was then forbidden from consorting with other prostitutes, or they would face hefty compensation fees.

Oiran vs Geisha

Oiran and Geisha are often confused due to their similar cultural contexts, but they hold distinct roles, attire, and makeup within Japanese society. I wrote a full and comprehensive guide explaining the differences of Oiran vs Geisha.

What is an Oiran?

Oiran were high-class courtesans in Japan, particularly during the Edo period (1603-1868). They were the pinnacle of the yūjo, and entertained guests with their skills in dance, music, and conversation. As the most elite of all courtesans, Oiran were expected to have exceptional beauty and education in various arts.

Oiran wore opulent kimonos as you can see from my photos, typically heavily adorned with intricate patterns and embroidery. They donned multiple layers of silk, with the outermost layer being the most elaborate. Their obi (sash) was tied in the front, which was a unique characteristic of Oiran, and they wore tall, wooden platform sandals called koma-geta or oiran-geta.

Oiran wore striking makeup, characterized by a thick white foundation made from rice powder, bold red lips, and dramatic eyes with red and black accents. Their eyebrows were elongated and shaped into a gentle curve.

What is a Geisha?

Geisha, also known as geiko in Kyoto, are professional entertainers skilled in traditional Japanese arts such as dance, music, and tea ceremonies. They have been part of Japanese culture since the 18th century and continue to play a significant role today. Geisha are known for their elegance, refined mannerisms, and profound knowledge of various arts and traditions.

Geisha wear simpler kimonos compared to Oiran, often in subdued colours and patterns. Their obi is tied at the back, and the length of the obi varies depending on the region. Geisha wear white tabi (split-toe socks) and traditional wooden sandals called okobo or zori.

Geisha makeup is characterized by a white foundation made from rice powder, but it is applied in a thinner layer than that of Oiran. They accentuate their eyes with black liner and red eyeshadow, while their lips are painted in red, typically in a smaller shape to create an illusion of a delicate mouth. Geisha fill in their eyebrows with charcoal, giving them a softer and more natural appearance.

Oiran were high-ranking courtesans with opulent attire and makeup, while Geisha are skilled entertainers who showcase refined aesthetics and a profound understanding of traditional Japanese arts.

Are tourists allowed to wear kimono in Japan?

Yes, tourists are allowed to wear kimono in Japan, as long as you wear it with respect and admiration. Our kimono experience was facilitated by Japanese locals who were keen to share their culture with us and tell us all about it. Many Japanese people loved seeing us in a kimono, passers-by, and patrons from the tea house requested to take pictures with us.

You can rent a kimono in Kyoto or Tokyo, from dedicated kimono houses that help foreigners dress beautifully in a kimono.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is a kimono left over right?

Yes, a traditional kimono is worn with the left side overlapping the right side. This is the standard way of wearing a kimono for both men and women. The left-over-right style is considered to be proper and auspicious, and it is followed in various Japanese customs and ceremonies, such as tea ceremonies, weddings, and other formal events.

There is one exception to this rule, and that is when a kimono is worn in the right-over-left fashion. This style is reserved specifically for the deceased during funerals or other related ceremonies. Wearing a kimono right-over-left in any other situation is considered inappropriate and disrespectful.

When putting on a kimono, it is important to follow the proper sequence of steps to ensure the garment is worn correctly:

Put on the undergarments (such as a nagajuban),

Put on the kimono itself

Add the obi (a wide sash that helps keep the kimono closed)

Add any other accessories.

Adjust the collar and overall fit of the kimono to ensure that the left side is overlapping the right one

What is the purpose of a kimono?

The kimono is a traditional Japanese garment with both practical and cultural significance. Its purpose has evolved, and it has come to embody various aspects of Japanese society, art, and tradition.

Clothing: The primary purpose of a kimono is to serve as a piece of clothing, literally meaning “the thing to wear” in Japanese language. A kimono offers coverage and protection from the elements. Kimonos are made from various fabrics, including silk, cotton, and synthetic materials, and can be worn in different seasons and for many occasions.

Cultural and social significance: The kimono holds a prominent place in Japanese culture, symbolizing the country’s rich history and traditional values. The patterns, colours, and motifs on a kimono can convey information about the wearer’s social status, marital status, or personal taste. The art of wearing a kimono, known as kitsuke, also reflects an individual’s etiquette, refinement, and understanding of Japanese customs.

Ceremonial and special occasions: Kimonos are worn during formal events and ceremonies, such as weddings, funerals, tea ceremonies, and other traditional gatherings.

Art and craftsmanship: Kimonos are considered works of art, showcasing intricate craftsmanship and design. The process of making a kimono can be labor-intensive, involving dyeing, weaving, and embroidery techniques. Many kimonos feature elaborate and beautiful patterns, representing nature, seasons, or traditional symbols.

Performance and dance: In traditional Japanese performing arts such as Kabuki theatre, Noh, and classical dance, kimonos are an essential part of the performers’ costumes, helping to convey characters and emotions on stage.

Is a kimono worn by a man or a woman in Japan?

Kimonos are worn by both men and women in Japan, though the styles, designs, and patterns differ between the two genders.

Men’s kimonos are typically simpler and more subdued in colour and design compared to women’s kimonos. They usually feature solid colours or small, subtle patterns. A man’s kimono is often worn with a hakama, which is a type of pleated, skirt-like garment worn over the kimono. Men’s obi, the wide sash used to secure the kimono, are also simpler and narrower than women’s obi.

Women’s kimonos tend to be more elaborate and colourful, with intricate designs and patterns. The style of the kimono and the choice of accessories can vary depending on factors such as the age, marital status, and the formality of the event. For example, young, unmarried women typically wear furisode, a type of kimono with long, flowing sleeves that signify their availability for marriage. Married women typically wear tomesode, which has shorter sleeves and more subdued patterns. Women’s obi are wider and more ornate, and they can be tied in various intricate knots to enhance the overall appearance of the kimono.

What is a kimono called?

A kimono (着物) is a traditional Japanese garment characterized by its straight-seamed, T-shaped design, long, wide sleeves, and a wrap-around style that is secured with a wide sash called an obi. The term “kimono” literally means “thing to wear” in Japanese, with “ki” (着) meaning “to wear” and “mono” (物) meaning “thing.”

Some examples of different types of kimonos include:

Furisode (振袖): A kimono with long, flowing sleeves, typically worn by young, unmarried women.

Tomesode (留袖): A kimono with shorter sleeves and more subdued patterns, commonly worn by married women.

Yukata (浴衣): A casual, lighter-weight kimono made of cotton or synthetic fabrics, worn by both men and women during informal events or summer festivals.

Is it disrespectful to wear a kimono if your not Japanese?

As long as a kimono is worn with a genuine sense of reverence and admiration for the rich and diverse Japanese culture, it is absolutely acceptable for someone who isn’t Japanese to wear a kimono.

It is important to be mindful of the cultural significance of the garment, the etiquette of wearing it, and to approach the experience with humility and respect. If a non-Japanese person takes the time to learn about and respect these aspects, it demonstrates an appreciation for the culture rather than an attempt to exploit or misrepresent it.

That being said, it is crucial to be sensitive to the feelings of others and to consider the context in which you choose to wear a kimono.

To understand the controversy surrounding the issue, it is crucial to consider the cultural significance of the kimono in Japan. The kimono is a traditional Japanese garment that has been worn for centuries and is steeped in cultural and historical significance. It is often worn for special occasions, such as weddings and festivals, and is a symbol of Japanese identity and cultural heritage.

Proponents of cultural appreciation argue that wearing a kimono as a non-Japanese person can be a way to celebrate and appreciate Japanese culture. They believe that wearing a kimono can help to promote cultural understanding and respect, and can be seen as a form of cross-cultural exchange.

However, opponents of non-Japanese people wearing kimonos argue that cultural appropriation can be harmful and disrespectful. They argue that wearing a kimono without understanding its cultural significance or without respecting its origins can be seen as a form of exploitation or commodification of Japanese culture. They also point out that historically, Japan has been subject to cultural exploitation and appropriation by Western powers, which makes it all the more important to respect and honour the cultural traditions of Japan.

Ultimately, cultural exchange is about sharing and celebrating the beauty and diversity of different traditions, and as long as this is done with respect and understanding, wearing a kimono as a non-Japanese person can be a positive and enriching experience for everyone involved.

Are kimonos meant to be revealing?

Traditionally, kimonos are not meant to be revealing. In fact, they are designed to be quite modest and cover the body completely. Kimonos are usually made of a single piece of fabric and are often worn over a slip called a nagajuban, which is also designed to cover the body.

The shape of the kimono is quite loose and flowing, which allows for ease of movement and comfort. The neckline of the kimono is typically high and conservative, and the sleeves are quite long, covering the hands.

While there are some modern adaptations of the kimono that may be more revealing, such as those worn by geishas or for certain special occasions, these are not representative of the traditional kimono. The traditional kimono is meant to be a modest garment that is worn for formal and ceremonial occasions.

Leave a Reply