Ever noticed those little red stamps on official papers in Japan? Those are called Hanko, and they’re a big deal here. Far from just a quirky tradition, these stamps are used all over the country to sign important documents, open bank accounts, and even add an official touch to artwork.

In this article, we’re going to break down what Hanko stamps are, why they’re still so popular, and how you can get one yourself. Whether you live in Japan or are just visiting, this guide to hanko has everything you need to know.

What is a hanko?

A hanko or inkan is a traditional personal seal used extensively in Japan for authenticating documents, contracts, and official paperwork. While much of the world has transitioned to electronic signatures and digital means of verification, Japan has held on to this time-honoured practice. Made from a variety of materials like wood, plastic, and occasionally more controversial materials like ivory, the hanko is carved with the name of an individual or organization. To use it, you simply press the hanko into an ink pad and then onto the document, signifying approval or confirmation.

The Japanese hanko typically features the user’s last name carved in Kanji characters and is designed to be small—usually less than 2cm across—making it easy to carry around. Customization is a key element of the hanko. Not only is your name or surname carved into it, but you can also choose from various shapes and designs. The most common shapes are circular, oval, and square, though the overall design is generally rod-like.

Speaking of ink, the ink used for hanko is typically red. The colour red has cultural significance in many East Asian societies, often symbolizing good luck and protection against evil spirits. In the context of documents and official paperwork, the red ink stands out clearly, making the seal easy to identify.

Types of Hanko

While the fundamental purpose of a hanko remains consistent—to authenticate—a range of types exists, each tailored for specific uses or levels of formality. Here’s a closer look at these types:

Jitsuin

The “jitsuin” is the most formal and official type of hanko. Generally made from high-quality, durable materials, this seal is registered with the local government and serves as a legally binding signature. You would use a jitsuin for major life events or significant financial transactions like getting married, buying a house, or signing a business contract.

Ginkōin

If you have a bank account in Japan, you’ll likely be introduced to a “ginkōin,” a hanko specifically designed for banking transactions. Although not as formal as a jitsuin, a ginkōin is still vital as it’s associated directly with your financial activities. This seal is kept securely but separate from the jitsuin, often in a different case or location, to prevent accidental misuse.

Mitomein

For everyday tasks that require less formality, the “mitomein” is the go-to hanko. These are often made of less expensive materials and are widely available at stationery stores. You’d use a mitomein for non-critical documents like acknowledging a delivery at work or signing internal company memos. Unlike its more formal counterparts, the mitomein doesn’t require official registration and can be easily replaced if lost.

Rakkan-in

Less known, Rakkan-in refers to the official stamp used to authenticate works of Japanese art, such as paintings and calligraphy. Historically, the artist would place this seal at the bottom corner of a painting or at the end of a piece of calligraphy. Alongside the seal, artists write their actual name, an alias, their social status, or the date when the artwork was completed.

Artists specializing in calligraphy or painting may use multiple hanko seals to sign their creations. These hanko can either bear the full name of the artist, a part of it, or even their artistic moniker. In English terminology, they’re commonly referred to as “artist chops.”

History of hanko

The tradition of using personal seals as a form of signature started in China and eventually spread to Japan. Initially in Japan, hankos were exclusively used by the Emperor, symbolizing his authority.

During the 8th century, the usage extended to the noble class for formal transactions. Later, during the feudal era (1085-1603), samurais adopted the hanko, distinguishing themselves by using red ink.

A significant shift came during the Meiji period (1868-1889). Amid rapid modernization, hankos became an everyday tool for all Japanese citizens, facilitated by a new law that set up a nationwide registration system for these personal seals.

Japanese Hanko today

Even though the Japanese government has been actively trying to curb the use of hanko because of the Covid pandemic, hanko continues to play an important role in Japanese society, for now. Chances are, we will still get to see the use of hanko for a few more years even though the government has been removing the use of hanko for over 15,000 types of administrative processes. That’s great progress!

Still, many foreigners who move to Japan continue to purchase hanko. It just makes us feel less like outsiders and more like we belong. You can visit a hankoya which is a small specialized hanko shop in Japan or you can order one from a larger chain. Even your local Don Quijote has them.

The only thing you need to remember is that your hanko must feature some element of your name. Whether you decide to carve your full name, solely your surname, or just your given name, the characters used must correspond to your legal name.

And from experience, remember that if you have a foreign name, your hanko has to have your name etched in either the Latin script or in katakana. To avoid any complications, you should go with Latin script. If you do want to be cooler and have katakana, then please remember that your name in katakana should be officially recorded somewhere, in your residence card or somewhere official; otherwise the office will likely reject it. And yes, before you get your hopes up, your name in hanki will be rejected by the office.

Who needs a hanko?

If you’re just visiting Japan, you do not need a hanko. However, you might want to consider getting one as a souvenir.

If you live in Japan you might one to get a hanko though. While a hanko isn’t strictly essential for everyone, it can offer a sense of belonging and smooth out some bureaucratic processes in Japan. If you don’t engage in activities requiring formal contracts, such as property purchases or business agreements, you might not technically need one.

However, owning a hanko can help you avoid awkward situations where your foreigner status becomes glaringly evident. Without a hanko, you might encounter uncomfortable pauses or subtle signs of inconvenience, followed by the reluctant acceptance of a signature as an alternative. For many foreigners, having a hanko eliminates this, making interactions seamless and more integrated into the local culture.

If you find yourself in a pinch requiring a hanko, don’t worry. The process from customization to registration is generally swift, often completed within two or three days, sometimes even less.

What is the cost of a hanko in Japan

You can always go to a local hanko shop in your neighbourhood, but they are increasingly rarer. Nostalgic places like Yanaka Ginza still have them, though. Nowadays, the simplest way to get a hanko is to order it online. You will notice that most websites are not in English so you will either need some help or you might want to use Google Translate for your ease.

The process for ordering a hanko is very easy and prices start from as little as ¥2250. You can get them made of wood or acrylyc. Of course, if you need a hanko for your fancy company, you might want to consider titanium, agate, crystal or chrysolite. These cost in the region of ¥25000.

I’m just kindly asking you to consider that some hanko shops offer ivory or other animal horns (like buffalo and cow) as an option, which I strongly advocate against. There is really no need to use animal products for something as trivial as stamps. High-quality wood or precious stones are way cooler and more impressive. If you really want something unique and special, splurge on a getting a precious metal hanko instead.

Note: Be careful when picking the size and typeface to ensure they translate well to romanji or katakana.

Where will you come across a hanko

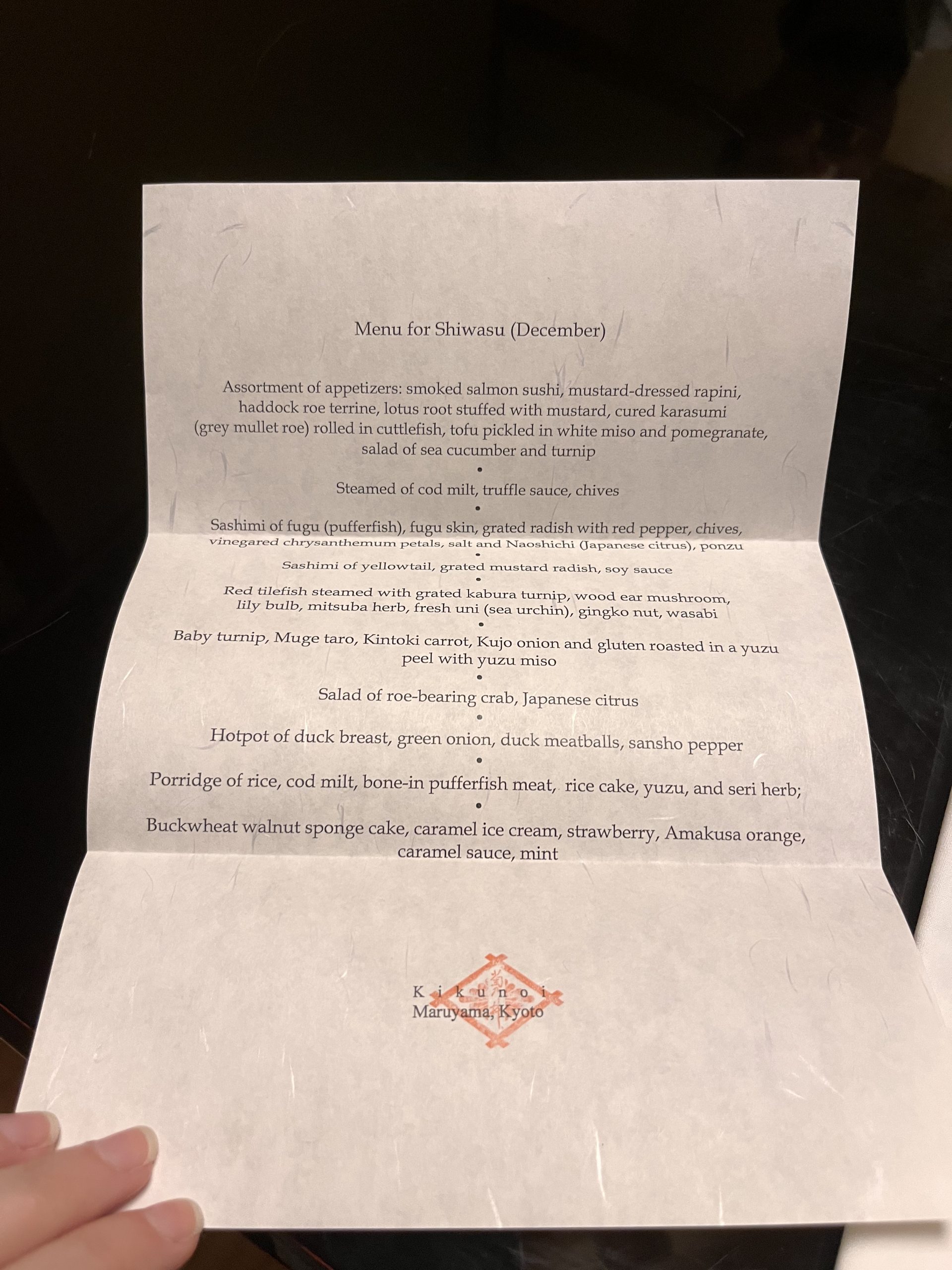

Whether you live in or just visiting Japan, chances are you’re going to come across hanko. You might even find it that a specific restaurant uses it on their menu. For example, Kikunoi in Kyoto uses their hanko as you can see in the picture below.

There are also hanko available at most temples and points of interest. When visiting Japan, it’s common to get a little blank notebook and fill it up with lots of hanko from places you visited. It’s a really nice memo from the country.

And of course, if you do decide to do business in Japan, open a bank account or purchase real estate, chances are you will see plenty of hanko.

Hanko as a souvenir

You’ve decided that you don’t need a hanko but you still want one as a souvenir. I totally get it, you can come across hanko and inkan everywhere in Japan, so naturally you want to leave your own stamp (see what I did there?).

If you’re on the hunt for an affordable but memorable gift, Hanko stamps are an excellent option. Easily found in 100-yen shops or the ubiquitous Don Quijote stores, these compact seals won’t break the bank or take up much space in your luggage. They’re a low-cost but high-impact way to share a slice of Japanese culture.

Whether you opt for the round or square shape, you can get up to 7 or 12 English letters, respectively, etched on them. Plus, the range of seven different fonts adds another layer of customization.

From Kointai’s rounded simplicity to Kissoutai’s ancient Chinese-inspired characters, the choice of font style allows you to tailor the Hanko to the recipient’s personality. Choose Tenshotai for balanced symmetry or Gyoshotai for bold brushstrokes. If you’re after something unique, Soshotai brings the flair, while Kaishotai offers a classic square look often seen on postcards. The stamp even comes in a case that includes an ink pad, completing the gift set.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can foreigners have a hanko?

Yes, foreigners can have a hanko, and many do, especially those who live in Japan for an extended period. A hanko serves as a personal seal and is used in various contexts like signing documents, opening bank accounts, and even receiving packages. It essentially acts as your signature and is a legally recognized form of identification in Japan.

When a foreigner moves to Japan and needs to handle official paperwork or open a bank account, having a hanko can make these processes smoother. Some banks and government offices still require a hanko for certain transactions or paperwork, so owning one can be beneficial.

You can have your hanko made with your name transliterated into katakana, which is the script commonly used for foreign names in Japan. Alternatively, you could use the Latin alphabet, but make sure the name on the hanko matches the name on your official identification.

Obtaining a hanko is relatively straightforward. You can visit specialized hanko shops or order one from larger stores or online. Customization options range from the material used (wood, stone, etc.) to the type of script (katakana, Latin letters).

Note: While it’s possible to have a hanko, it’s not strictly necessary for all foreigners. Depending on your activities in Japan, you might get by using a traditional signature, but having a hanko can offer a greater sense of belonging and ease in navigating certain bureaucratic processes.

Does every Japanese have hanko?

Not every Japanese individual necessarily owns a hanko, but it is extremely common and almost a cultural expectation for adults to have one. The hanko serves as a personal seal used in place of a signature for various official and unofficial documents. In Japan, they are often used for tasks ranging from signing for a package to closing a business deal.

There are different types of hanko for different purposes. For example, a “jitsuin” is a registered seal often used for important documents like contracts, and a “ginkōin” is typically used for banking. A “mitomein” is a more casual hanko for everyday, less formal tasks.

While younger generations and some businesses are moving towards digital verification methods, the hanko system is still deeply rooted in Japanese society. However, some procedures that used to require a hanko are now being modernized to accept electronic signatures, partly accelerated by remote work conditions brought about by the pandemic.

Is a hanko a signature?

In Japan, a hanko serves a similar purpose to a handwritten signature. A hanko is a physical stamp that is pressed into an ink pad and then onto a document to signify approval or consent. It is used for various official and non-official purposes, from acknowledging receipt of a package to signing contracts. The hanko typically contains the user’s surname in Kanji, Katakana, or sometimes even in Roman characters.

While signatures are used widely in many parts of the world, the traditional Japanese system has relied on the hanko for similar purposes.

Leave a Reply