Dive into the world of Japanese food, where every dish is a celebration of fresh, seasonal, and regional ingredients. In our first week in Japan, we discovered a whole new world of flavours. We slurped up bowls of hearty ramen, savoured the freshness of handmade sushi, and indulged in desserts that were as unique as they were tasty.

What makes Japanese food stand out is its attention to detail. Popular Japanese food doesn’t just taste incredible, but looks fantastic, as it is standard practice to combine the art of food aesthetics with the science of flavour fusion. And I’m not just talking about expensive restaurants, but all the food in Japan looks unbelievable. The top notch Japanese food aesthetic is prevalent even when it comes to street food, or affordable ramen joints.

When it comes to food in Japan, it’s not just about eating, it’s about experiencing a culture. And remember, you can’t really go wrong with Japanese food. Even the smallest, most unassuming izakayas serve up hearty, delicious meals with excellent customer service. In fact, even your local konbini will have perfect ready-made meals that will blow you away. So, before you set off on your Japanese adventure, take some to learn how to behave in a Japanese restaurant and spend a little time familiarizing yourself with all Japanese manners. It will make your journey all the more enjoyable and memorable.

Popular Japanese food

When we discuss popular Japanese food, we’re referring to the dishes that have not only won the hearts of locals but have also gained global recognition for their unique flavours, presentation, and the skill involved in their preparation.

Throughout the centuries, skilful chefs have perfected the art of cooking to such an extent that Japan ranks second behind France as having the most Michelin-star restaurants in the world. Cooking is seen as a mastery by the Japanese, and a good deal of abandon the office life to pursue the dream of opening an eatery.

Japanese cuisine is more than just food; it’s a reflection of the country’s culture and spirit. From the precision of sushi preparation to the comforting simplicity of a bowl of ramen, each dish tells a story of innovation and a relentless pursuit of perfection. This passion has positioned Japan as a top destination for food lovers worldwide.

The roots of Japanese cuisine can be traced back to the Jomon period (14,000-300 BC), when the diet primarily consisted of fish, shellfish, wild game, and plants. The introduction of rice cultivation during the Yayoi period (300 BC-300 AD) marked a significant shift in the Japanese diet, and it remains a staple food even today.

The Asuka period (592-710) saw the introduction of Buddhism, which greatly influenced Japanese cuisine. The Buddhist philosophy of non-violence led to a decrease in the consumption of meat, and vegetarian cuisine, known as Shojin Ryori, became prevalent, especially in monastic communities.

The Heian period (794-1185) saw the development of a unique Japanese food culture, with the creation of dishes like sushi and sake. The Edo period (1603-1868) brought about a culinary revolution, with the establishment of sushi as we know it today, and the popularization of foods like tempura and soba.

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), Japan opened its doors to the West, leading to the introduction of Western ingredients and cooking methods. This period saw the birth of dishes like Tonkatsu and Japanese curry, which are now considered quintessentially Japanese.

Post World War II, Japan saw a rapid economic growth that influenced its food culture. The country embraced convenience, leading to the popularity of instant ramen and conveyor belt sushi.

So, what can you expect from popular Japanese food? Expect a culinary journey that engages all your senses. Here are some of the must-try dishes that showcase the best of what Japanese cuisine has to offer.

Sushi

Sushi, a hallmark of Japanese cuisine, is often the first thing that comes to mind when I think of Japan. This association is deeply ingrained, painting a vivid picture of Japanese locals enjoying these flavourful rolls in sushi bars across the country.

Sushi is more than just a dish; it’s a culinary art form with a lot of history. Its origins can be traced back to the 8th century, when it was first used as a method of preserving fish in fermented rice. Over time, this evolved into the sushi we know today: a delightful combination of vinegared rice, fish, and vegetables, often wrapped in a sheet of nori (seaweed).

In Japan, you’ll encounter a wide variety of sushi. Makizushi, a popular type, consists of fish or vegetables rolled in rice and a nori sheet.

Temaki, is a cone-shaped sushi made of seaweed, filled with sushi rice, fish, and vegetables. For a unique experience, try gunkan, a type of sushi where a strip of dried seaweed encircles a mound of rice, topped with sea urchin or fish roe.

The creation of sushi is taken very seriously in Japan, with dedicated sushi chefs, known as itamae, who view their work as a form of art. As a diner, it’s important to respect this artistry by following certain customs and adhering to Japanese dining etiquette.

For example, you should avoid spilling sushi toppings. If you need to add more soy sauce, pick up a small amount of shoga (pickled ginger) to brush on your sushi. To cleanse your palate, eat a little pickled ginger or have a little tea. Make sure to not dip sushi rice in soy sauce and by the way, pulling off the topping is the greatest insult to the sushi chef!

Sashimi

Sashimi had always intrigued me. The idea of eating raw fish was foreign to me, probably because I was used to cooking seafood thoroughly before eating. But sashimi defies this norm. It’s simply raw fish, served in delicate slices, accompanied by a small garnishes.

The history of sashimi dates back to the Heian period (794 to 1185), when it was served at court banquets. The term “sashimi” means “pierced body”, which refers to the practice of piercing the fish’s tail and fin with a knife to identify the fish species.

You can find a variety of sashimi, from tuna and salmon to octopus and squid.While sashimi is most commonly associated with seafood, it can also be made from a variety of other ingredients. Here are a few examples:

- Basashi: This is horse meat sashimi, a speciality of Kumamoto Prefecture on the island of Kyushu. The meat is typically served cold, thinly sliced, and often accompanied by soy sauce and ginger.

- Torisashi and Toriwasa: These are chicken sashimi and semi-cooked chicken sashimi respectively. While it might sound unusual to many, in Japan, where poultry is often raised under strict conditions, these dishes are not unusual.

- Gyusashi: This is beef sashimi, which can be found in yakiniku (Japanese barbecue) restaurants. The beef is often high-quality wagyu, served raw and thinly sliced.

When eating sashimi, the first thing you’ll notice is the presentation. Sashimi is served on a platter, often with garnishes like shredded daikon radish, shiso leaves, or even real flowers. The arrangement is visually stunning, showcasing the natural beauty of the fish or meat.

When you take your first bite of sashimi, you’ll be struck by the freshness. The flavour is clean and pure, allowing the natural taste of the fish or meat to shine through. Unlike sushi, there’s no rice or other ingredients to complement or contrast with the main ingredient. It’s all about the sashimi itself.

The texture of sashimi is another key part of the experience. Depending on the type of fish or meat, it can range from buttery soft (like fatty tuna) to slightly chewy (squid or octopus).

It goes without saying that the key to enjoying sashimi, regardless of the type, is freshness. The ingredients must be of the highest quality and prepared with utmost care. This ensures not only the best taste but also safety when consuming raw or semi-cooked meats. This precisely why many people, myself included, have sashimi in places like Tsukiji and Toyosu in Tokyo which are renowned for having the freshest fish, quite literally caught on the same day.

Ramen

Having tried Japanese ramen in Western restaurants, I thought I knew what to expect. But the real deal in Japan was a different, and far more delicious, experience. Ramen is a beloved dish in Japan, a comforting bowl of noodles swimming in a flavourful broth, topped with a variety of ingredients.

The story of ramen starts with Chinese immigrants who brought the dish to Japan in the late 19th century. Over time, it evolved, taking on a distinctly Japanese identity and branching out into regional variations that reflect the unique tastes and ingredients of different parts of the country.

In the chilly north of Hokkaido, you’ll find miso ramen, a robust, warming dish that’s perfect for warding off the winter cold. The broth is made with miso paste, giving it a rich, complex flavour that’s beautifully complemented by toppings like corn, butter, and hearty slices of chashu pork.

Head to Tokyo, and you’ll encounter shoyu ramen, a soy-based version that’s a staple in the city. The clear, brown broth is typically paired with curly noodles, and the dish is finished with a variety of toppings, including bamboo shoots, green onions, and a soft-boiled egg.

Travel to Hakata, a district in Fukuoka city, and you’ll be greeted by the creamy, rich broth of tonkotsu ramen. Made by boiling pork bones for hours, the broth is milky white and deeply flavourful, served with thin, straight noodles and minimal toppings.

Each bowl of ramen is a reflection of its locale, using local ingredients and flavors. So, trying ramen across Japan becomes a culinary journey, offering insights into the country’s diverse food culture. And trust me, once you’ve had a taste of authentic Japanese ramen, there’s no going back.

Miso Soup

Miso soup is a cornerstone of Japanese cuisine, a dish that’s as comforting as it is flavourful. At its core, miso soup is a simple combination of miso paste and dashi, a type of broth. And because of its salty, umami flavours, I find it simply addictive.

Miso itself is a fermented paste made from soybeans, salt, and a type of fungus called koji. The fermentation process can take anywhere from a few weeks to several years, resulting in a range of flavours from sweet and mild to salty and rich. Miso has been a staple in Japanese cooking for over a thousand years, with its origins dating back to the country’s Asuka period.

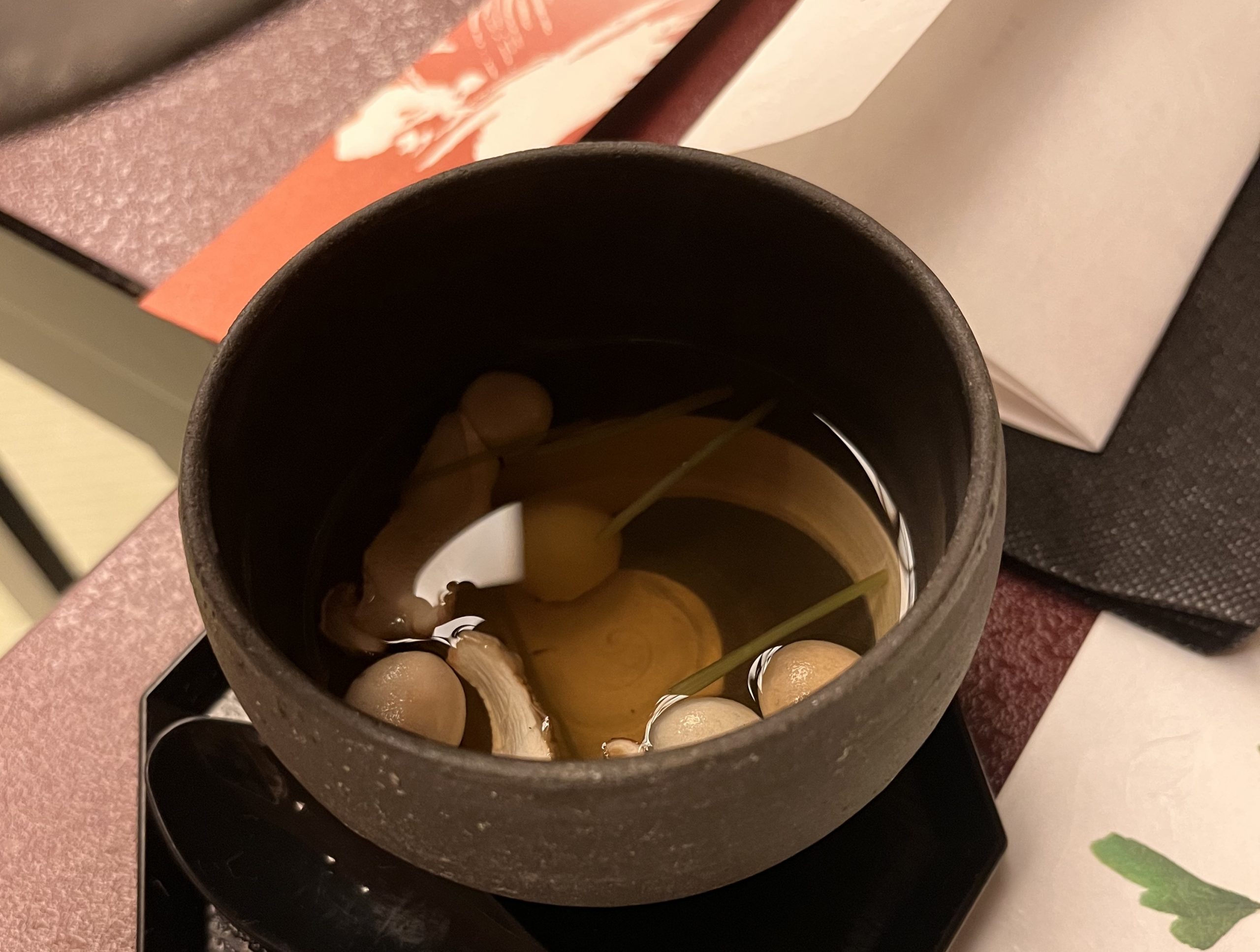

Miso soup is traditionally served as part of a Japanese breakfast, providing a warm, savoury start to the day. It’s also a common accompaniment to lunch and dinner meals, especially if you order a rice based dish like tonkatsu. The soup often includes additions like tofu, green onions, and wakame seaweed, but the ingredients can vary based on personal preference and regional styles. During dinner at Nishiyama Onsen, our miso was clear with mushrooms and clams in it. Delightful!

To enjoy miso soup for breakfast, simply serve it alongside other traditional Japanese breakfast foods (like rice, seaweed and grilled fish).

When eating miso soup, please remember that solid ingredients should be eaten with chopsticks, while the broth is sipped directly from the bowl. This might feel a bit unusual if you’re used to Western-style soups, but it’s all part of the experience.

Tempura

Tempura is a popular Japanese dish that’s essentially deep-fried meat or vegetables in a light, crispy batter. From vegetables like sweet potatoes and bell peppers to seafood such as shrimp and squid, almost anything can be transformed into a delicious tempura. Some of the best tempura I’ve had was actually in Kyoto at a restaurant called Hanasaki Manjiro.

The history of tempura is quite fascinating. While it’s a staple in Japanese cuisine today, its roots can be traced back to Portugal. In the 16th century, Portuguese traders and missionaries introduced the concept of deep-frying food to Japan. The Japanese then adapted this technique to suit their own culinary style, creating what we now know as tempura.

Eating tempura is a delight. The contrast between the crunchy exterior and the soft, cooked interior of the ingredients makes for a satisfying bite. Tempura is typically served with a dipping sauce called tentsuyu, made from dashi, mirin, and soy sauce. A bit of grated daikon radish is often added to the sauce, adding a refreshing touch that balances out the richness of the fried food.

Tempura is versatile and can be enjoyed in various ways. You can have it on its own as a main dish, or as a side dish to complement other Japanese dishes. One popular way to enjoy tempura is with soba, buckwheat noodles (we’ll discuss it further below in this article). This dish, known as tempura soba, combines the crispiness of tempura with the earthy, nutty flavour of soba, creating a meal that’s both hearty and delicious.

Yakitori

Yakitori is a very popular Japanese dish and it’s essentially skewered chicken grilled over charcoal. The term “yakitori” can be broken down into “yaki”, which means to grill, and “tori”, the Japanese word for bird. It’s a simple dish, but one that’s packed with flavour.

The history of yakitori is closely tied to the rise of street food culture in Japan. It started gaining popularity in the post-war period, as a quick and affordable food option. Today, it’s a beloved part of Japanese cuisine, enjoyed in restaurants, at home, and in street food stalls known as yatai.

Eating yakitori is straightforward. It’s typically served on skewers, making it easy to eat. You can enjoy it with a simple sprinkle of salt or a brush of tare sauce, a sweet and savoury glaze that adds an extra layer of flavour.

For the best yakitori experience, head to Shinjuku in Tokyo. This bustling district is known for its nightlife and food scene. Here, you’ll find Omoide Yokocho, also known as “Memory Lane”, a narrow alley lined with tiny yakitori stalls. There’s also Golden Gai, a network of six alleyways known for its eclectic mix of bars and eateries, where you can enjoy yakitori along with a drink.

Another great spot is Ebisu Yokocho, an indoor food alley in the stylish neighbourhood of Ebisu. Here, you can hop from one stall to another, trying different types of yakitori along with other Japanese delicacies.

Okonomiyaki

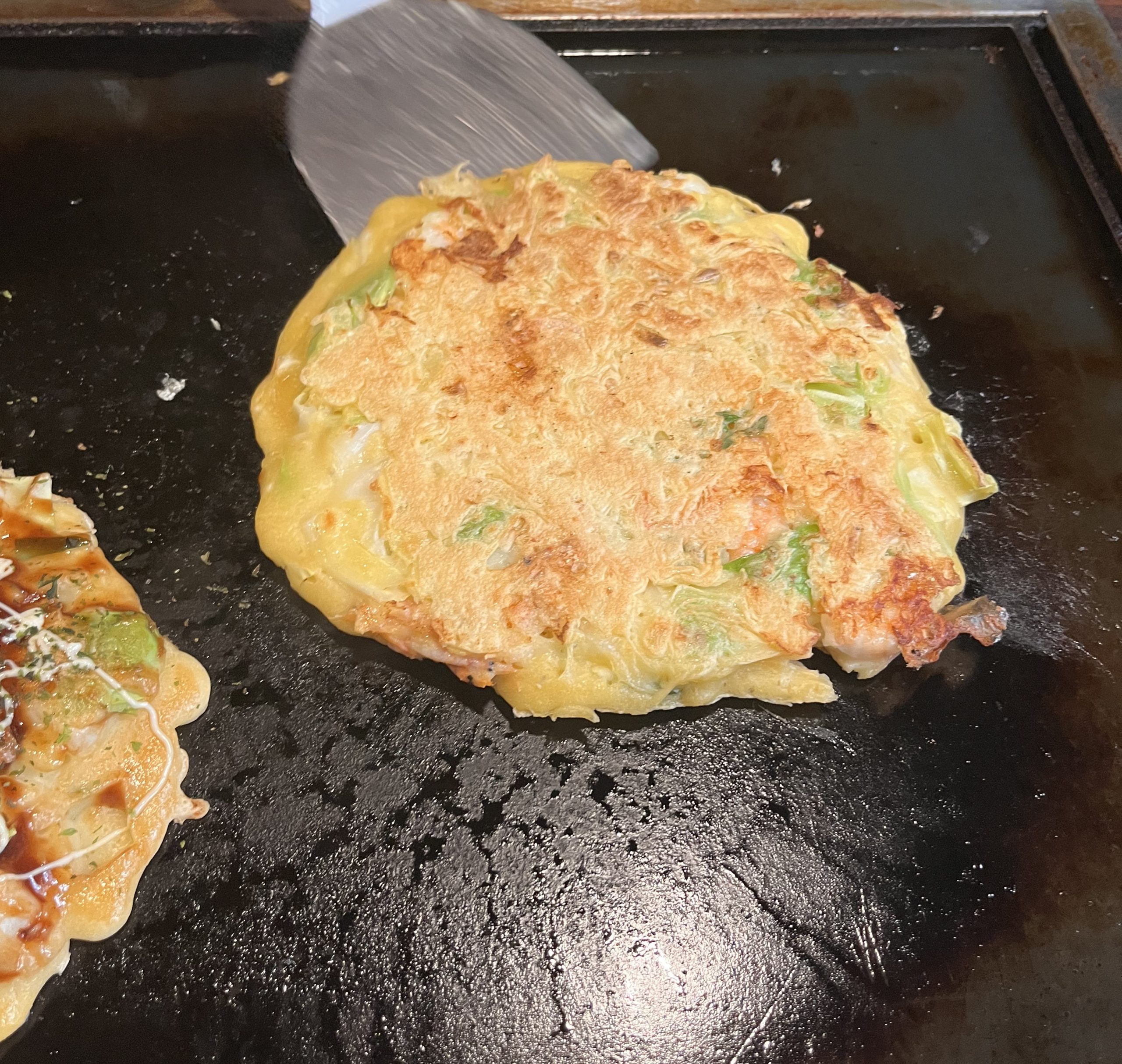

Okonomiyaki is a savoury Japanese pancake that’s as fun to eat as it is to say. The name “okonomiyaki” comes from “okonomi”, which means what you like, and “yaki”, meaning grilled. This is a nod to the dish’s versatility, as it can be filled with a variety of ingredients based on your preference.

The history of okonomiyaki dates back to the 16th century, with a thin crêpe-like dish called funoyaki. This evolved into a popular confection for children in the Meiji era, known as monjiyaki, which involved drawing with flour batter on a griddle and adding chosen ingredients. The term “okonomiyaki” first appeared in an Osaka shop in the 1930s, and the dish gained popularity post-World War II as an affordable and filling meal. Over time, regional variations developed, including the issen yōshoku of Kyoto, which may have influenced the modern savoury version of okonomiyaki.

Today, okonomkiyaki is a beloved part of Japanese cuisine, particularly in the regions of Hiroshima and Osaka, each known for their unique take on the dish. Hiroshima, though, has more okonomiyaki restaurants per capita than any other region in the country.

In Osaka, the style of okonomiyaki is similar to a pancake, with all the ingredients mixed into the batter before being cooked. It’s typically topped with okonomiyaki sauce, mayonnaise, dried seaweed, and bonito flakes.

Hiroshima-style okonomiyaki, on the other hand, is more like a layered crêpe. The ingredients are cooked separately, then layered and topped with a generous serving of noodles. It’s a hearty, satisfying dish that’s a must-try when visiting the city.

Eating okonomiyaki is a casual affair. It’s often cooked right in front of you on a hot griddle, allowing you to watch as your meal comes together. Once it’s ready, just dig in with your chopsticks and enjoy. And if you’re feeling adventurous, you can even make your own okonomiyaki in the beautiful restaurant of Sometarō located in Asakusa, Tokyo.

Takoyaki

Takoyaki is a popular Japanese street food that’s as tasty as it is unique. These are ball-shaped snacks made from a wheat flour-based batter and cooked in a special moulded pan. The star ingredient is “tako”, or octopus, which is chopped into small pieces and added to each ball. Just careful, as they are always very hot! Takoyaki is especially popular in Osaka, where you can find them at many stalls around Dotonbori.

The history of takoyaki goes back to the 1930s in Osaka, a city known for street food culture. A street vendor named Tomekichi Endo is credited with its invention. He was inspired by a similar dish called akashiyaki, a dumpling from Hyogo Prefecture, and decided to create his own version using octopus, hence the name “takoyaki”.

While octopus is the traditional filling for takoyaki, variations do exist. However, since takoyaki literally means grilled octopus, for it to be a true takoyaki, the balls must have octopus.

Eating takoyaki is a must when visiting Japan. It’s typically served piping hot with a variety of toppings, including takoyaki sauce (similar to Worcestershire sauce, but thicker), mayonnaise, green onions, and bonito flakes. The outside is crisp, while the inside remains soft and gooey, creating a delightful contrast of textures.

Tonkatsu

Tonkatsu is a classic Japanese dish that’s all about comfort and flavour. It’s a breaded, deep-fried pork cutlet, served with shredded cabbage, rice, miso and a tangy sauce. The name “tonkatsu” comes from “ton”, meaning pig, and “katsu”, short for “katsuretsu”, the Japanese word for cutlet.

The history of tonkatsu dates back to the late 19th century, during the Meiji era, a time when Japan was opening up to Western influences. The dish was initially called “katsuretsu” or simply “katsu”, and it was originally made with beef. It wasn’t until the early 20th century that pork became the meat of choice, leading to the dish we know today as tonkatsu.

The dish is usually served with a side of rice, pickles, miso soup and a heap of shredded cabbage, which adds a refreshing crunch to balance out the richness of the fried pork. The tonkatsu sauce, similar to Worcestershire sauce but thicker and sweeter, is a crucial component, adding a tangy contrast to the savoury pork. When you order tonkatsu, most restaurants offer free refills of rice, cabbage, and miso. I have two favourite restaurants which serve fantastic tonkatsu: Tonkatsu Maisen Aoyama and Katsukura located in the train station in Kyoto.

Tonkatsu is made by taking a thick slice of pork loin or tenderloin, coating it in flour, dipping it in beaten egg, and then covering it in panko breadcrumbs. The breaded pork is then deep-fried until it’s golden brown and crispy on the outside, while remaining juicy on the inside. Restaurants offer a variety of pork meats, some juicier and more tender than others. In Maisen restaurant, they use specialty pork–Amai-Yuwaku also known as Sweet Temptation, Japanese Kurobuta (black pig) by Okita-san, and Tea-leaf fed pig called Chamiton.

Soba

Soba is a type of Japanese noodle made from buckwheat flour. These noodles are thin, long, and have a distinctive earthy flavour that sets them apart from other types of noodles. Soba can be served either cold with a dipping sauce or hot in a soup, making it a versatile dish. Personally, I love them served cold with dipping sauce on the side.

The history of soba dates back to the Edo period in Japan, where it was enjoyed by people of all social classes. Its consumption was particularly beneficial in preventing beriberi, a disease caused by thiamine deficiency, which was common among the wealthier population who primarily consumed white rice.

When eating soba, it’s common to slurp the noodles. This isn’t considered rude, but rather a way to enhance the flavour and enjoy the noodles fully. If you’re eating cold soba, you’ll dip the noodles into a soy-based sauce before eating.

Don’t confuse soba with udon. Udon noodles are made from wheat flour, which gives them a softer, chewier texture and a milder flavour compared to soba which are thicker and made from buckwheat.

Udon

Udon is a type of thick, chewy noodle that’s a staple in Japanese cuisine. Made from wheat flour, water, and salt, udon has a mild flavour and a satisfyingly chewy texture that makes it a versatile base for a variety of dishes.

The history of udon is believed to date back over a thousand years, with many attributing its introduction to Buddhist monks who brought the noodle-making technique back from China. Over the centuries, udon has become a beloved part of Japanese food culture, with different regions developing their own unique variations.

Eating udon can be a slurpy affair. The noodles are often served in a soy-based broth with various toppings like green onions, tempura, and tofu.

While they share some similarities, udon is very different to ramen. Ramen noodles, which are also made from wheat, are thinner and have a springy texture, served in a rich broth. Udon, on the other hand, are thicker and have a softer, chewier texture. The broth for udon is lighter, made from a simple combination of soy sauce, mirin, and dashi.

Unagi No Kabayaki

Unagi no Kabayaki is a classic Japanese dish featuring grilled eel, and before I tell you more about it, I’m here to tell you that’s also one of the most delicious foods. “Unagi” is the Japanese word for freshwater eel, and “kabayaki” refers to the method of preparation, which involves skewering the eel, grilling it, and glazing it with a sweet soy-based sauce.

The eel is tender and rich, and the sweet-savoury glaze adds a layer of complexity to the dish. It’s typically served over a bed of warm rice, allowing the sauce to seep into the grains for an extra burst of flavor.

In the Kantō region of eastern Japan, the eel for kabayaki is slit down its back, butterflied, cut into shorter fillets, skewered, and then grilled, steamed, and grilled again with flavouring, resulting in a tender and flaky texture. In contrast, in the Kansai region of western Japan, the eel is slit down the belly, grilled directly without steaming, often in its original length, resulting in a tougher, chewier skin, which can be tenderized by placing it between layers of hot rice.

Gyoza

Gyoza is a type of Japanese dumpling that’s a favourite in homes and restaurants across the country. These crescent-shaped dumplings are filled with ground meat (usually pork) and vegetables, then wrapped in a thin dough. Gyoza is usually pan-fried to a delicious crisp.

Gyoza has its roots in Chinese dumplings. In China, gyoza (called jiaozi in Chinese) is commonly cooked and eaten boiled. It was introduced to Japan during World War II by soldiers returning from China. Over time, the Japanese adapted the recipe to their tastes, creating a unique version that’s now a staple of Japanese cuisine.

Gyozas are usually served with a dipping sauce made from soy sauce, vinegar, and chili oil. The contrast between the tender filling, the soft dough, and the crispy bottom (if pan-fried) creates a wonderful mix of textures and flavours.

If you wish to eat gyoza in Japan, most ramen joints will have them as starters on their menu.

Shabushabu

Shabu-shabu is a delightful Japanese hot pot dish that’s more…interactive. The name “shabu-shabu” is an onomatopoeia, mimicking the sound of ingredients being swished around in a pot of boiling broth.

The origins of shabu-shabu are relatively recent compared to other Japanese dishes. It’s considered a variant of the traditional nabemono or Japanese hot pot, with a focus on thinly sliced meat.

Eating shabu-shabu is a hands-on experience. The dish is served with thinly sliced beef, although you can see other types of meats or even seafood. Alongside the meat, there are a variety of vegetables, tofu, and sometimes noodles. These ingredients are cooked piece bypiecer at the table in a pot of hot, flavourful broth.

To enjoy shabu-shabu, you take a slice of meat, swish it around in the boiling broth until it’s cooked to your liking (which can be just a few seconds for thin slices), then dip it in a flavourful sauce before eating. The vegetables and other ingredients are also cooked in the broth, adding to the depth of flavour.

Fugu

Fugu (pufferfish), is a unique Japanese delicacy that’s famous for its potential dangers. The fugu fish contains a potent neurotoxin, which can be lethal if the fish isn’t prepared correctly. This makes eating fugu a thrilling culinary adventure for those who dare.

The history of fugu consumption in Japan is a long one, with records dating back hundreds of years. However, due to the risks associated with eating the fish, there were periods in history when the Japanese government banned its consumption. Today, chefs must undergo rigorous training and earn a special licence to prepare and serve fugu, ensuring the safety of diners. This usually involves a 2-3 year apprenticeship and a thorough examination process

You normally eat fugu as sahimi to really enjoy its delicate flavour and slightly chewy texture. It can also be served in a hot pot, grilled, or even used to make sake known as hirezake.

When dining on fugu, it’s common to start with the sashimi, appreciating the subtle flavour and texture of the fish. The hot pot, if ordered, is enjoyed next, allowing the broth to take on the flavour of the fugu. If you’re feeling adventurous, you might end the meal with hirezake, which is warm sake served with the grilled fin of the fugu.

Mochi

Mochi is a type of Japanese rice cake that’s cherished for its chewy texture and subtle sweetness. And let’s face it, it’s the most well-known Japanese dessert, too. Mochi is made from a special type of sticky rice called mochigome, then usually filled with sweet bean paste, matcha paste or fruit jellies.

The history of mochi stretches back to the Yayoi period (300 BC to 300 AD), when it was a food of the gods and used in religious offerings. Over time, mochi became a symbol of good fortune and a staple of New Year’s celebrations in Japan. Today, it’s enjoyed year-round and you can find it in every konbini in Japan, as well as in international Asian stores around the world.

Making mochi involves soaking and steaming the mochigome before it’s pounded into a smooth, sticky dough. This process, known as mochitsuki, is often a communal event where people take turns pounding the rice with large wooden mallets. Nowadays, you will find factory-manufactured mochi and some newer inventions which use ice cream as filling.

Dango

Dango is a traditional Japanese sweet and my favourite treat in Japan. Dangos are round dumplings, made from rice flour, skewered on bamboo sticks and come in a variety of flavours and colours, making them a popular choice for street food.

The history of dango dates back over a thousand years, making it a long-standing part of Japanese culinary tradition. It’s often associated with the changing seasons. For example, during the cherry blossom season, you might find hanami dango, a tricoloured dango that’s a popular snack for cherry blossom viewing parties. The best dango I’ve ever had was from Shibamata, Tokyo during the cherry blossom season and let me tell you: life changing. So delicious, with yuzu paste!

Dangos can be flavoured with a variety of ingredients, from sweetened soy sauce to red bean paste, and even green tea. Some types of dango are grilled, giving them a deliciously smoky flavour and slightly crispy exterior. By now, you’ve probably guessed that I’m a huge fan of dango flavoured with yuzu paste.

Kaiseki Ryori

Kaiseki Ryori is a special type of Japanese meal. It’s a traditional dinner with multiple courses that highlights the very best of Japanese cooking. It’s a dining experience that’s as much about the aesthetic presentation and seasonal themes as it is about the food itself. In fact, kaiseki influenced the multi-course fancy dinners in many Michelin restaurants.

The origins of Kaiseki Ryori can be traced back to the tea ceremony traditions of the 16th century, where a simple meal was served to prevent tea-drinkers from becoming too hungry. Over time, this meal evolved into an elaborate dining experience, with a focus on seasonal ingredients, meticulous preparation, and beautiful presentation.

Eating Kaiseki Ryori is a journey through the seasons and the local landscape. Each course is designed to highlight the flavours and textures of seasonal ingredients at their peak.

Kaiseki Ryori is a multi-course Japanese meal that follows a specific sequence. It begins with Sakizuke, an appetizer that sets the tone for the chef’s style. The Hassun course follows, setting the seasonal theme. Suimono, a soup made from dashi stock, cleanses the palate. Mukozuke or Otsukuri is a plate of premium seasonal sashimi. Takiawase is a vegetable dish served with meat, fish, or tofu. Futamono, a second soup course, is served in a lidded dish. Yakimono is a course of flame-grilled seasonal fish. Shiizakana, meaning “strong snack,” are small dishes meant to be enjoyed with sake. Gohan or Shokuji is a seasonal rice dish, often cooked in a clay hot pot. Tome-wan is a vegetable or miso soup, often served alongside the previous rice dish. The meal concludes with Mizumono, a platter of seasonal Japanese desserts, featuring items such as fruit, confections, ice cream, and cake.

Each dish is served in individual portions and presented in carefully chosen dishware that complements the food and the season.

Chankonabe

Chankonabe is a hearty Japanese stew that’s famously associated with sumo wrestlers. It’s a nutritious, protein-packed dish designed to help these athletes gain weight and maintain their strength. So I’m sure you can appreciate why it’s not my go-to dishes while in Japan, although I’m not going to lie, it’s pretty delicious and comforting in the winter.

The history of chankonabe is closely tied to the world of sumo. It’s traditionally prepared by junior sumo wrestlers for their seniors in the communal kitchens of sumo stables. While there’s no fixed recipe for chankonabe, it includes a variety of high-protein ingredients like chicken, fish, tofu, and vegetables, all simmered together in a flavourful broth.

Natto

Natto is a traditional Japanese food with a unique taste and texture. It’s made from fermented soybeans and has a strong, distinctive smell, a sticky texture, and a flavour that can be described as nutty and slightly tangy. It looks slightly unappealing as it does look a little slimy. But give it a go, it’s so delicious. In fact, natto is one of my favourite Japanese foods. I have it every morning, with a poached egg as my breakfast.

The history of natto goes back over a thousand years in Japan, with some theories suggesting it was introduced by the Chinese or developed independently in multiple regions. Despite its long history, natto was not always universally loved in Japan due to its strong smell and taste. However, it has gained popularity in recent years due to its health benefits, including being a good source of protein and probiotics.

Making natto involves soaking, steaming, and fermenting soybeans with a bacteria called Bacillus subtilis. The process takes several days and requires careful temperature control to ensure successful fermentation.

Matcha

Matcha is a type of powdered green tea that has a central role in Japanese culture, particularly in traditional tea ceremonies. The history of matcha in Japan dates back to the 12th century, when it was brought over from China by Buddhist monks. It quickly became a staple in monasteries and eventually found its way into the wider society. The preparation and consumption of matcha became a spiritual practice, culminating in the development of the Japanese tea ceremony.

The tea is traditionally prepared by whisking the powder with hot water in a bowl until it becomes frothy. The result is a rich, creamy tea with a balance of sweet and bitter flavours. It’s often served with a small sweet treat to complement the tea’s bitterness.

Making matcha involves a careful process of shading the tea plants to increase their chlorophyll content, hand-picking the leaves, and grinding them into a fine powder. This labor-intensive process contributes to the tea’s high-quality and distinct flavour.

In Japan, matcha is well-loved and prevalent in everyday sweets and drinks, too. A trip to any konbini will reveal a whole new world of matcha including matcha jellies, gums, mochi, nuts and even chocolate. There are even restaurants which specialise in serving matcha ice cream and matcha tiramisu layer cakes.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are popular Japanese foods?

Japan has so many wonderful dishes you ought to try. The good news is that during your next visit to Japan, you can actually try them all. Food in Japan is affordable and delicious, whether you try it from a konbini or high-class restaurant. Here are popular Japanese foods to try:

Sushi: Vinegared rice topped with various ingredients like raw or cooked seafood, vegetables, or rolled egg.

Ramen: Wheat noodles served in a savoury broth, topped with slices of pork, vegetables, and other garnishes.

Tempura: Deep-fried seafood, vegetables coated in a light and crispy batter.

Yakitori: Skewered grilled chicken or other meats.

Sashimi: Fresh slices of raw fish or seafood, served with soy sauce and wasabi.

Miso Soup: A traditional soup made with soybean paste, tofu, seaweed, and other ingredients.

Tonkatsu: Breaded and deep-fried pork cutlet.

Udon: Thick wheat noodles served in a hot or cold broth.

Sukiyaki: A hot pot dish made with thinly sliced beef, vegetables, and tofu, cooked in a sweet and savoury soy-based broth.

Okonomiyaki: A savoury pancake made with cabbage, flour, and toppings like meat, seafood, and vegetables.

Takoyaki: Octopus-filled batter balls, cooked on a special griddle and topped with sauce, mayonnaise, and bonito flakes.

Onigiri: Rice balls typically filled with ingredients like pickled plum, grilled salmon, or seasoned seaweed.

Gyoza: Pan-fried dumplings filled with minced meat and vegetables.

Soba: Thin buckwheat noodles, served hot or cold, with dipping sauce.

Yakiniku: Grilled meat cooked at the table and dipped in savoury sauces.

Oden: A simmered dish with tofu, fish cakes, and vegetables cooked in a soy-based broth.

Matcha: Finely powdered green tea, used in traditional tea ceremonies.

Kaiseki: A multi-course traditional Japanese meal similar to Michelin type restaurants.

Shabu-shabu: Thinly sliced meat and vegetables cooked by dipping them into a boiling broth.

Nabe: A hot pot dish with meat, seafood, tofu, and vegetables cooked in a flavourful broth.

Chawanmushi: A savoury egg custard dish steamed with ingredients like shrimp, mushrooms, and chicken.

Katsudon: A bowl of rice topped with a breaded and deep-fried pork cutlet, egg, and onions.

Somen: Thin wheat noodles, usually served cold and dipped into a soy-based sauce.

Taiyaki: Fish-shaped pastries filled with sweet red bean paste, custard, or other fillings.

What are the top 10 Japanese dishes?

The top 10 Japanese dishes can vary depending on personal preferences, but here are my favourite Japanese foods:

Sushi

Ramen

Matcha desserts

Tempura

Tonkatsu

Sashimi

Yakitori

Udon

Miso Soup

Okonomiyaki

What is basic Japanese food?

Basic Japanese food consists of staple ingredients and dishes that are commonly found in everyday meals across Japan. Rice (Gohan) is a fundamental component of Japanese meals and serves as the main source of carbohydrates. Miso Soup is served with many rice dishes and is a simple and comforting soup made with miso paste, tofu, seaweed. Fish, such as mackerel or salmon, is often marinated and grilled, and served with a side of rice and miso soup. Tofu is very prevalent in Japanese cuisine, often enjoyed in various forms like silken tofu, firm tofu, or deep-fried tofu (agedashi tofu). Soy sauce and seaweed are considered staple ingredients too.

Leave a Reply