The evolution and diversity of Japanese cinematography are deeply rooted in its cultural heritage, drawing significantly from traditional art forms and societal transformations. Early influences like haiku poetry have shaped its narrative style, evident in the works of directors like Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu. Japanese cinema splits into realism and fantasy, exploring the nation’s identity and history.

Samurai cinema, led by Akira Kurosawa, parallels the Western genre, while directors like Shohei Imamura delve into Japan’s societal changes post-war. The genre landscape extends to yakuza films, surrealism, and the bold narratives of pink and ultra-violent cinema, each pushing societal norms and viewer sensibilities.

Japanese animation, or anime, has made a significant global impact, with pioneers like Osamu Tezuka and Hayao Miyazaki leading the charge. Contemporary Japanese cinema, with directors like Hirokazu Kore-eda and Naomi Kawase, continues to resonate globally, highlighting the dynamic and diverse nature of Japanese film.

It’s a fascinating subject, and in this article, I’m on a mission to uncover more about the evolution of pictures in Japan.

The role of Haiku

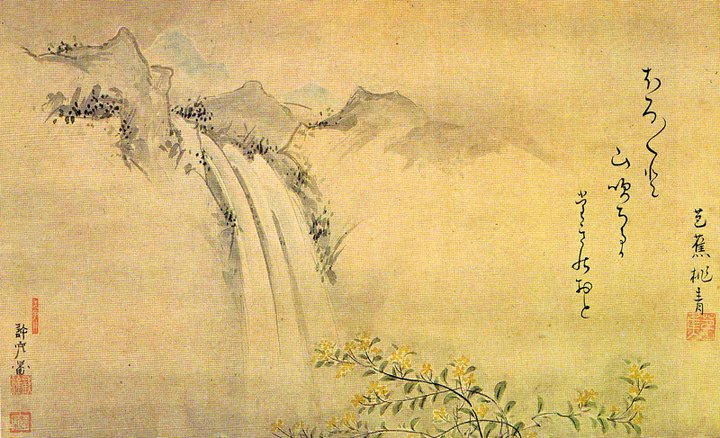

The early influence of haiku poetry, with its emphasis on brevity and imagery, played a foundational role in shaping the narrative and visual style of Japanese films. Directors like Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu pioneered this integration, using the juxtaposition of shots to narrate visually, akin to the layered meanings found in haiku. This poetic influence marked the split of Japanese cinema into two primary schools: realism and fantasy, each exploring different aspects of Japanese identity and history.

What is more interesting is that even nowadays, the two schools continue to function in parallel with each other. Pick any Japanese film, and it will immediately be put in one of the two categories.

The realism in Japanese cinema found early expression in Mikio Naruse’s work, while fantasy was magnificently portrayed in Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu Monogatari, digging into historical themes that resonate with Japan’s cultural idiosyncrasy.

Samurai Cinema

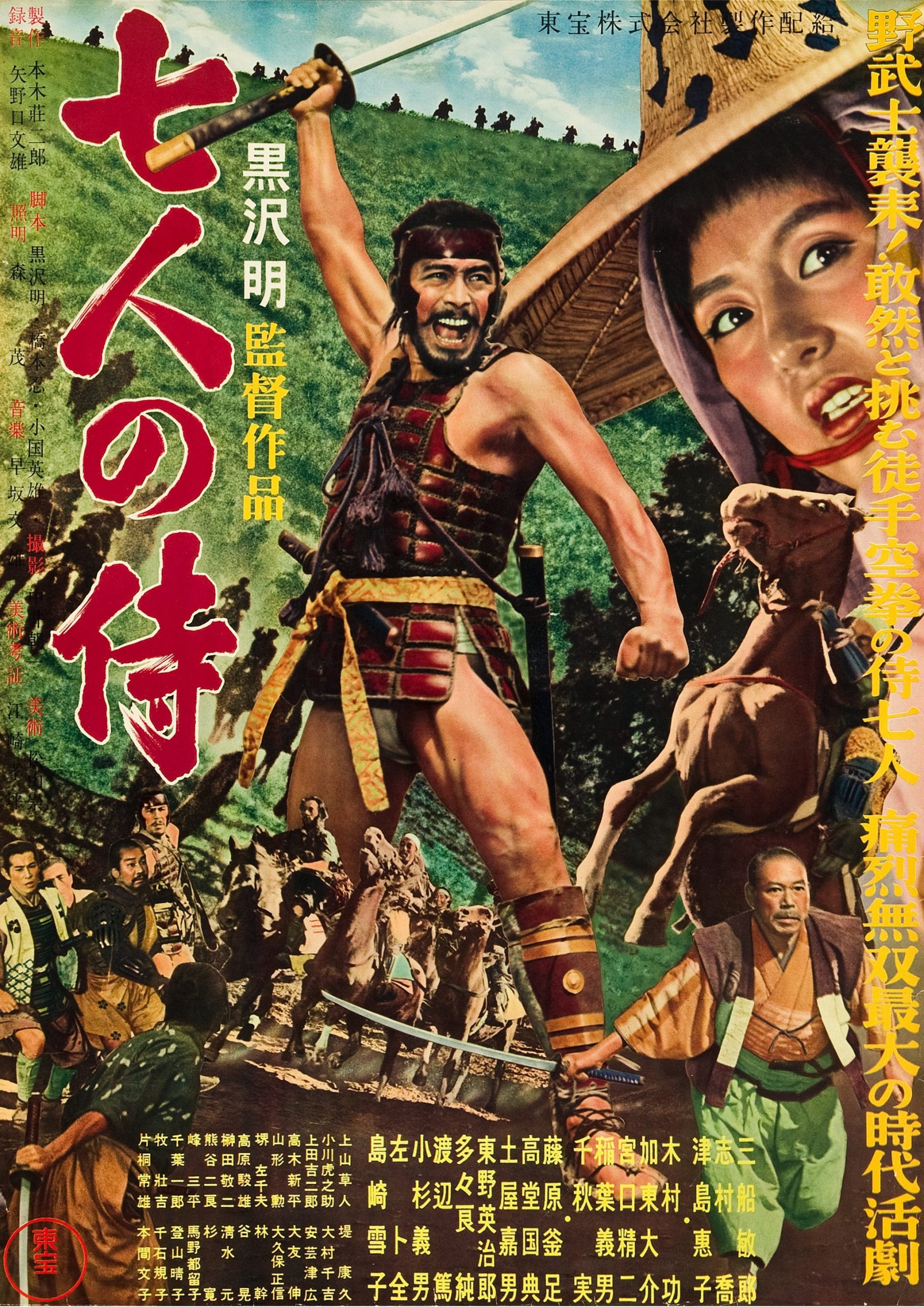

Samurai cinema, akin to the Western genre in Hollywood, became iconic with directors like Akira Kurosawa leading the way with films such as Yojimbo and Sanjuro. These films, alongside Masaki Kobayashi’s Hara-Kiri, celebrated traditional Japanese values and innovated in narrative structure, influencing cinema globally.

Kurosawa’s influence extended beyond samurai tales, as seen in his adaptations of Shakespearean tragedies and his contribution to various cinematic styles. His impact on global cinema is undeniable, with films like Star Wars drawing inspiration from his work.

In contrast, directors like Shohei Imamura questioned the very foundations of humanism in Japanese society, influenced by the country’s rapid economic transformation, in films such as “The Pornographers” and “The Ballad of Narayama.”

Storytelling

Yasujiro Ozu’s unique approach, often employing a camera positioned at a low, tatami-mat level, brought an intimate perspective to his storytelling, focusing on post-war Japanese society with simplicity and depth. His work, especially “Tokyo Story,” is a testament to his mastery in portraying the nuances of human relationships and the inevitable generational divide. Tokyo Story is a film in the top 50 best films of all times. Now that, is a great achievement!

War and anti-war

The exploration of anti-war themes became prominent post-World War II, with directors like Kon Ichikawa highlighting the futility and destruction of war. This period also saw the rise of genres like Yakuza films, which depicted the life and codes of the Japanese mafia, evolving over time to reflect changes in societal attitudes towards violence and crime.

Yakuza films

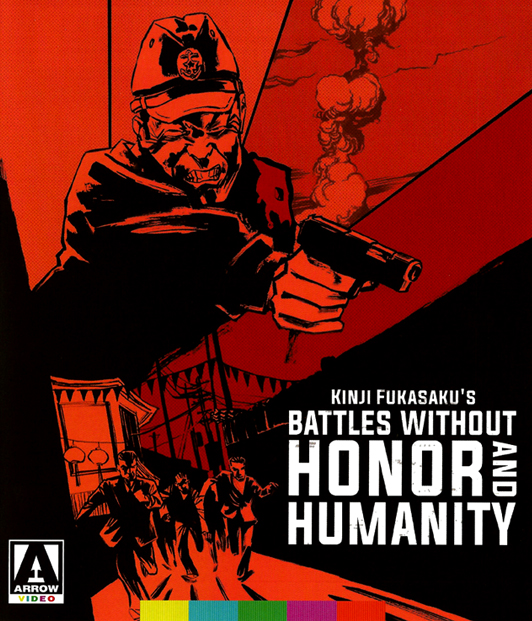

Yakuza films, a prominent genre within Japanese cinema, focus on the lives and dealings of yakuza, the members of organized crime syndicates in Japan. This genre encompasses a wide range of narratives, from the honour and brotherhood within yakuza families to the brutal reality of their criminal activities, often blending elements of action, drama, and tragedy.

The genre gained significant popularity in the post-war period, reflecting the social upheavals and moral ambiguities of the time. Directors like Kinji Fukasaku, Takeshi Kitano, and Seijun Suzuki are notable figures in yakuza cinema. Fukasaku’s “Battles Without Honor and Humanity” series in the 1970s is renowned for its gritty realism and depiction of the yakuza’s brutal internecine warfare. Takeshi Kitano’s “Outrage” series, on the other hand, offers a modern take on yakuza life, highlighting the power struggles and shifting alliances within contemporary organized crime.

Seijun Suzuki’s stylistically bold films, such as “Branded to Kill,” mix yakuza film conventions with surreal visuals and unconventional narratives, pushing the boundaries of the genre.

Japanese Surrealism

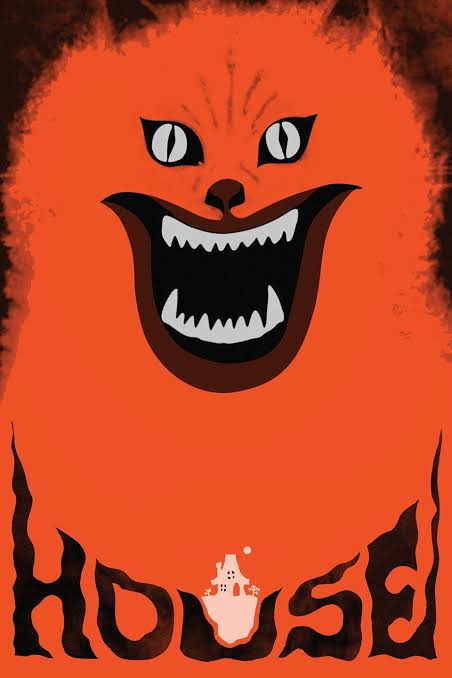

Japanese cinema’s foray into surrealism and horror brought international acclaim, with directors like Hiroshi Teshigahara and Nobuhiko Obayashi blending fantastical elements with profound human experiences. The evolution continued with the controversial yet captivating pink cinema, and the extreme narratives found in ultra-violent films, challenging both societal norms and viewers’ sensibilities.

Pink Cinema

Pink cinema, also known as “pink film” or “pinku eiga” in Japanese, refers to a genre of theatrical softcore adult films that emerged in Japan in the 1960s. These films typically blend erotic content with various film genres, often including comedy, drama, and occasionally horror or fantasy elements. Pink cinema became a significant part of Japanese filmmaking due to its low-budget nature, allowing for more creative freedom and experimentation among directors. Despite their erotic content, pink films are known for their artistic and narrative qualities, typically addressing themes like social taboos, human psychology, and personal relationships. Directors like Koji Wakamatsu and Masao Adachi were prominent figures in this genre, using it as a platform to explore political and social issues, thereby elevating the genre beyond mere exploitation cinema.

Ultra-violent films

Ultra-violent films in Japanese cinema refer to a sub-genre characterized by extreme violence, gore, and often graphic content, surpassing conventional action or horror films in intensity. This genre gained prominence in the late 20th century and includes films that push the boundaries of on-screen violence, often incorporating elements of horror, crime, and thriller genres. Directors like Takashi Miike and Sion Sono are notable figures in ultra-violent cinema, with films like “Audition” and “Suicide Circle” (also known as “Suicide Club”) respectively. These films use violence to explore deeper themes such as human nature, societal pressures, and the psychological aspects of violence, making them more than just showcases of gore and brutality. The ultra-violent genre has been both criticized for its graphic content and celebrated for its artistic approach to difficult subjects, contributing to a complex and multifaceted view of contemporary Japanese cinema.

Japanese Animation

The history of anime dates back to the early 20th century, but it was Osamu Tezuka, often referred to as the “God of Manga,” who played a pivotal role in its development during the post-war era. His work, along with the success of his creation “Astro Boy” (Tetsuwan Atomu) in 1963, laid the foundation for modern anime. Tezuka’s innovations in production techniques and storytelling, along with his prolific output, significantly shaped the anime industry.

Significant figures in the anime industry include Hayao Miyazaki, whose works like “My Neighbor Totoro,” “Spirited Away,” and “Princess Mononoke” have received international acclaim for their storytelling, animation quality, and thematic depth. Mamoru Oshii’s “Ghost in the Shell” and Katsuhiro Otomo’s “Akira” are landmark films in the science fiction genre, known for their complex narratives and pioneering animation techniques.

Anime has had a substantial global impact, influencing various forms of media and entertainment around the world.

Today, the anime industry continues to thrive, with an array of productions ranging from television series and films to web series and OVAs (Original Video Animations). Studios like Studio Ghibli, Toei Animation, and Madhouse are known for their high-quality productions.

Contemporary Japanese cinematography

Contemporary Japanese cinematography continues to be a dynamic and influential force in the global film industry, characterized by its diversity, innovation, and rich storytelling. Modern Japanese cinema encompasses a wide range of genres, including drama, horror, animation, and independent films.

Hirokazu Kore-eda is renowned for his poignant family dramas that explore the intricacies of human relationships and societal issues. His film “Shoplifters” (2018) won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and was acclaimed for its deep emotional impact and exploration of unconventional family structures.

Naomi Kawase is an influential filmmaker whose works delve into themes of nature, human connections, and personal identity. Films like “An” (2015) and “till the Water” (2014) display her lyrical and contemplative style.

Shinji Aoyama, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and Sion Sono are other notable directors who have made significant contributions to various genres, including thriller, horror, and avant-garde cinema, gaining both domestic and international recognition.

The animation sector remains robust, with Studio Ghibli continuing to be a significant player. Directors like Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata have left a lasting legacy, and the studio maintains its influence with its rich catalogue. Newer studios and filmmakers, such as Makoto Shinkai, whose works like “Your Name” (2016) and “Weathering with You” (2019) have achieved both critical acclaim and commercial success, are pushing the boundaries of anime in terms of storytelling and visual innovation.

Contemporary Japanese films continue to receive accolades at international film festivals, contributing to the global dialogue on cinema. Films like “Drive My Car” (2021) by Ryusuke Hamaguchi, which won an Oscar for Best International Feature Film, highlight the continued relevance and artistic vitality of Japanese cinema on the world stage.

Leave a Reply